Shortly after Prince Harry arrived in the U.S., he was quoted as saying—in an early encounter with American-style free speech—that it was “bonkers.” Do we really get to say whatever we want? Not exactly. In fact, dozens of court cases have put up fencing around our ideas of free speech. As far back as Alexander Hamilton, we’ve expended a lot of energy on the topic.

A Decade of Free Speech Tests

So…in our second dive into a discussion of America’s experiment with free speech, let’s move into the late 20th century to find other landmark Supreme Court decisions. Not surprisingly, several important rulings came about in the late ‘60s to early 70’s—during one of our biggest eras of protest speech.1

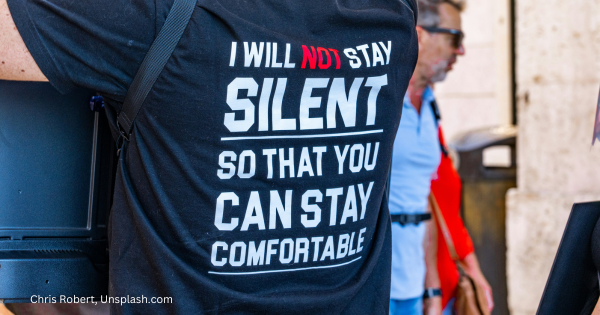

1969 – The Supreme Court moved to protect symbolic speech in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District.2 The district suspended several students for wearing black armbands to protest the Vietnam War. The Court ruled that the armbands, with silent protest, constituted so-called “symbolic speech” and was therefore protected under the Constitution.

In the same year, police arrested a speaker at a KKK meeting in Ohio. They charged him, and he was convicted of advocating criminal conduct. The Supreme Court ultimately overturned the conviction. In doing so, they added a new free speech test. They explained that for speech to be illegal, it had to promote “imminent lawless action” to be unconstitutional.3 It was a new standard by which to measure live speech-making.

1971 – The effects of the 60’s lingered for quite a few years, providing the Court with plenty of free speech cases. The Supreme Court narrowed the concept of so-called “fighting words,” when they reversed the conviction for Paul Cohen. He had worn a jacket with the words “F— the draft” on it. The Court ruled that since the language was not directed at any specific person, that it was protected by the free speech doctrine.

The Press Tests the Doctrine

Later that year, as portrayed in the movie The Post, The Washington Post prepared to publish parts of the Pentagon Papers. They were a collection of papers that revealed the machinations behind government decisions involving the Vietnam War.

The Supreme Court scrambled to hear the emergency case the government made to stop the presses. The Court ruled that the primary purpose of the First Amendment was to “prohibit the widespread practice of governmental suppression of embarrassing information.”

So, if the only purpose in prohibiting the Post from publishing some of the Pentagon Papers was to prevent the government from being embarrassed, then that wasn’t a good enough reason. The Court allowed the Post to print excerpts. The importance of this case was that it established the right of the press to extensive freedom without any fear of prior censorship, otherwise called “prior restraint.” So, The Post published the Pentagon Papers—excerpts, that is—because they were 7000 pages long!

The principle of abolishing “prior restraint” continued in the public discussion for a while.

The Most “Heinous” Form of Censorship

1976 – In Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart,4 Chief Justice Warren E. Burger wrote the majority opinion. In it, he stated that “prior restraints on speech and publication are the most serious and least tolerable infringement on First Amendments rights.”

The legal language can be hard to follow. Let’s paraphrase it:

Anyone attempting to control speech, whether in writing or oral presentation, in advance of the publication of that speech, is engaging in the most heinous infringement of our First Amendment rights that could be attempted.

The Court continued in this line of thinking into the 80’s.

Can Free Speech Be Curtailed in Schools?

1982 – Students from a school district in Levittown, NY, led by Stephen Pico, protested against books being taken from the school library. Among the list of banned books were some written by Kurt Vonnegut and Richard Wright. The School Board claimed that they were “anti-American.”

An appeals court reversed a lower court’s support for the school Board. The appeals court found that further study had to be made to determine whether the Board’s motivations were actually legal. For example, if they had been motivated to remove the books because they contained vulgarities, this motive would be legal. But if they had been motivated by an “impermissible desire to suppress ideas,” then the censorship would be illegal.

So the Supreme Court accepted the case. In Board of Education v. Pico5 the court ruled that school officials “may not remove books from school libraries because they disagree with the ideas contained in the books.” The court further stated that “the right to receive ideas is a necessary predicate to the recipient’s meaningful exercise of his own right of speech…and political freedom.” The majority opinion clarified that “students too are beneficiaries of this principle.”

It was another case of “prior restraint” in which the School Board decided whether the ideas were worth reading or not. And the Supreme Court upheld the students’ request to put the books back on the shelves.

Quick Summary

- Symbolic speech, such as on clothing, is OK.

- Speech that incites “imminent” danger to the public, is not OK.

- Censorship of ideas is never legal.

- BUT censorships of vulgarities or obscenities can be OK in a school setting.

- AND schools may not remove books only to suppress unpopular ideas.

We could study this topic for quite a while…but this is enough for now. What do you think?

- https://firstamendment.mtsu.edu/first-amendment-timeline/ ↩︎

- https://firstamendment.mtsu.edu/article/tinker-v-des-moines-independent-community-school-district/ ↩︎

- https://firstamendment.mtsu.edu/article/ku-klux-klan/ ↩︎

- https://firstamendment.mtsu.edu/article/nebraska-press-association-v-stuart/ ↩︎

- https://firstamendment.mtsu.edu/article/board-of-education-island-trees-union-free-school-district-v-pico/

↩︎

A Penny for Your Thoughts?